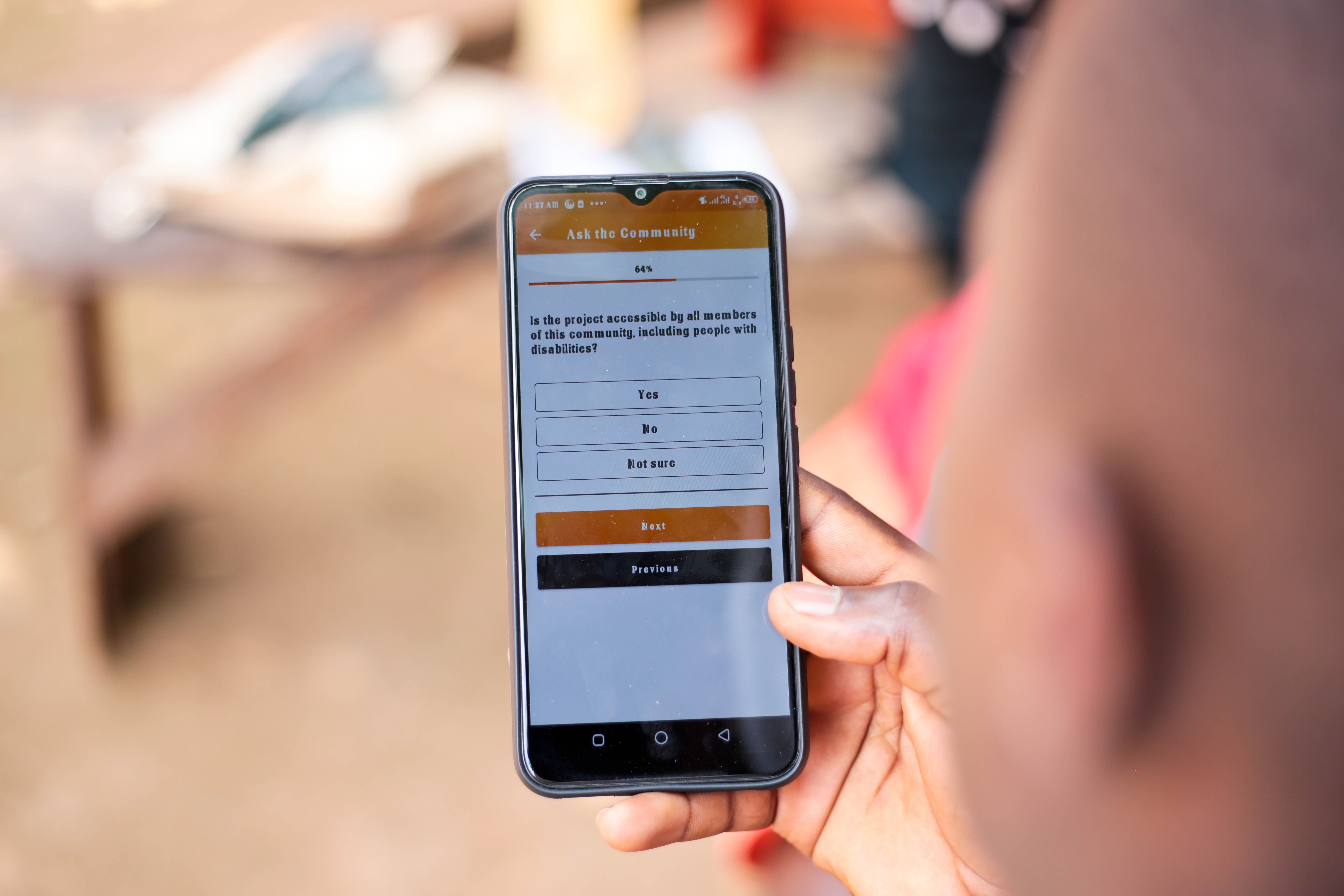

Integrity Action’s citizen monitoring app DevelopmentCheck in use. Photo Credit: Anthony Mwami/Restless Development

In late October 2020, Integrity Action launched an online brainstorm looking for ideas on how to sustain impact within social accountability. We were interested in what we call citizen-centered accountability (CCA) mechanisms, in which citizens provide feedback on services they are entitled to and ultimately hold them to account. We had two questions: how can they be funded in the long term? And how can they be governed or administered?

When we closed the survey five weeks later, we had 70 responses and a combined total of 8000 words covering suggestions, experiences, cautions, and various case studies to explore. In this blog, I will outline the main themes and some interesting examples based on some initial analysis. You can look out for the full analysis – alongside other findings from our sustainability research project – in the New Year. We are also working on publishing the full 8000 words in a more organized format – these ideas belong to everyone!

First, a note on who filled it out. 60% of respondents were from civil society, with the remainder made up of researchers, donors, and government. The prominence of civil society is unsurprising, given the networks we were tapping into and the level of interest in this topic among civil society practitioners. Geographically, Africa was the most represented continent, followed by Asia, and then people with a global scope of work.

How to fund it

What did the responses say? Out of the two broad questions we asked, we received considerably more ideas on funding models than on governance. The responses included:

- Establishing a local foundation to pool donor funding – this seemed to be viewed as a more robust way of generating and handling donor funding in the long term.

- A commercial business model, i.e., providing services to support the core functions of the accountability mechanism. Possibilities ranged from services that were more peripheral to the mechanism itself (such as consultancy services) to those more closely related to it (such as packaging community feedback information as marketing data – with an eye on consent and privacy concerns).

- More than one respondent referred to the money that CCA mechanisms are supposed to save – by preventing corruption or, say, shoddy infrastructure that needs more frequent repairs. Could this be leveraged to secure long-term funding? And can we establish how much money is saved anyway? (As it happens, Integrity Action is hoping to kick off some work on this in 2021 – watch this space.)

- Grassroots funding or “local philanthropy” also came up a few times. The concept of communities themselves contributing to valued local organizations or specific activities has gained traction recently, not only as a route to sustainability but also to “shift the power” in development funding and decision making.

As well as ideas, the survey had plenty of insights. One respondent wrote, “The ‘accountability culture’ of a context matters – in areas where this is nascent, I would guess long-term donor funding could have a great impact. In places where this element of the social contract is developed, then shifting towards more grassroots sources of funding could prove to be more sustainable financially and deepen this culture.”

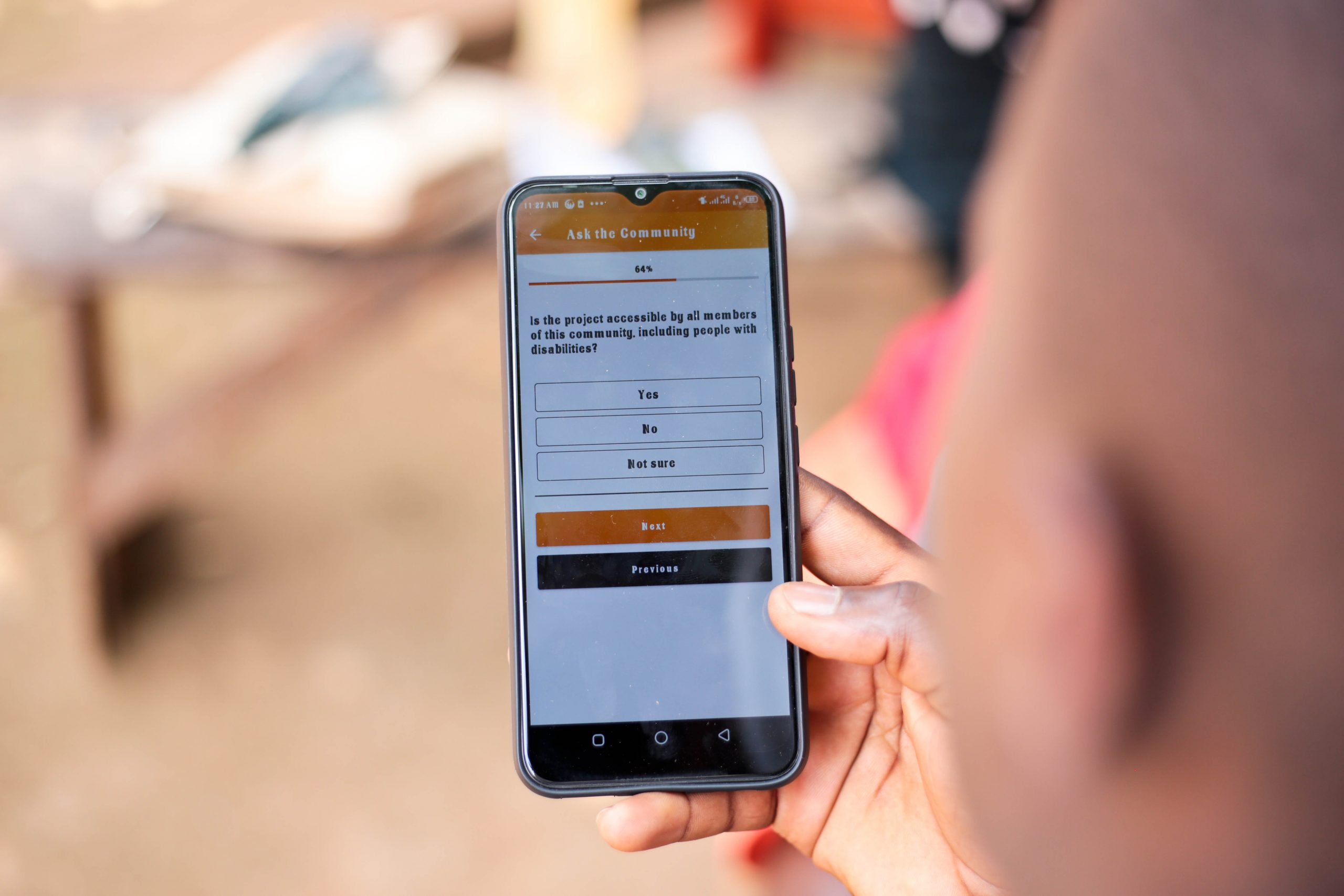

An image from Integrity Action’s animated case study on citizen monitoring in Afghanistan.

How to run it

Contributions to our second broad question, about how CCA mechanisms should be governed or administered in the long term, mostly looked at mechanisms established by civil society which involve government or service providers to different degrees.

This provided us with a range of interesting case studies. For example, the Civil Society Budget Advocacy Group in Uganda works with the Ministry of Finance to track how money is spent; Counterpart’s PRG-PA programme in Niger engaged citizens, unions, and government in the teacher assignment process; and CARE Egypt ran a social accountability project in cooperation with Egypt’s Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Development Agency.

Multiple respondents also mentioned more formal multi-stakeholder approaches, like the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative and the Open Government Partnership. These might seem a little “high level” when compared to the governance of specific accountability mechanisms, but let’s not forget the recent launch of OGP Local, which shows an exciting potential for bringing the multi-stakeholder approach closer to front-line duty bearers and communities. One respondent also cited ISAF (Implementation of the Social Accountability Framework) in Cambodia, which has a Partnership Steering Committee that is co-chaired by the Ministry of Interior and an NGO representative.

Meanwhile, transitioning a mechanism from civil society “ownership” into government hands was viewed with caution. One respondent referred to the likelihood of mechanisms “fizzling out” once civil society ceases to lead them; others highlighted the risk of co-optation and the need to have clear roles and responsibilities agreed upon from the start. However, occasional positive examples came through, such as Accountability Lab’s Civic Action Teams, a model which now has some level of co-ownership from 20 local governments globally.

It’s all very well, asking what the right model is for funding or governance, but a couple of respondents reminded us not to forget the human factor. One suggested we should be asking “whether citizens are, in fact, active users or simply expect others to engage in social accountability. Where there is a will, there will always be ways to overcome the material needs, but what sustains the will and consequent action?” This is one of the questions to be addressed in our full research report, which brings together inputs from the survey, 25 interviews with experts and practitioners, and a literature review. Please look out for that, as well as the full publication of the brainstorm contributions.

In the meantime, thanks to everyone who filled out the survey, as well as those who shared or promoted it – not least, the Transparency and Accountability Initiative! Please reach out if you have any further reflections to share: [email protected] / @dfthorne1.