This is a summary of a funding scan undertaken for a TAI funder member. TAI seeks to publicly share its research, but this work is not reflective of TAI’s or its member's views necessarily.

Check our related scan of Funding for issues related to corporate capture.

International tax justice is on the agenda as never before with the United Nations beginning negotiations and the implementation of a global corporate minimum tax.

There is no uniformly accepted definition of tax justice. From one perspective, tax justice sits at the intersection of various values about procedural, reparative, and distributive justice and human rights, seeking to promote the rights of citizens through progressive taxation within countries and increasing taxing rights for the Global South. Tax justice can also be an umbrella term for a variety of issues and proposals that have been supported by tax justice organizations, experts, and researchers, including stopping tax evasion and avoidance, increasing the progressivity of taxation, ending abusive tax treaties, and developing policy solutions to stop profit shifting to tax havens. Funders may only commit to some elements proposed under this rubric, and one key area of differentiation is whether negotiations under the Inclusive Framework are in the interest of the Global South.

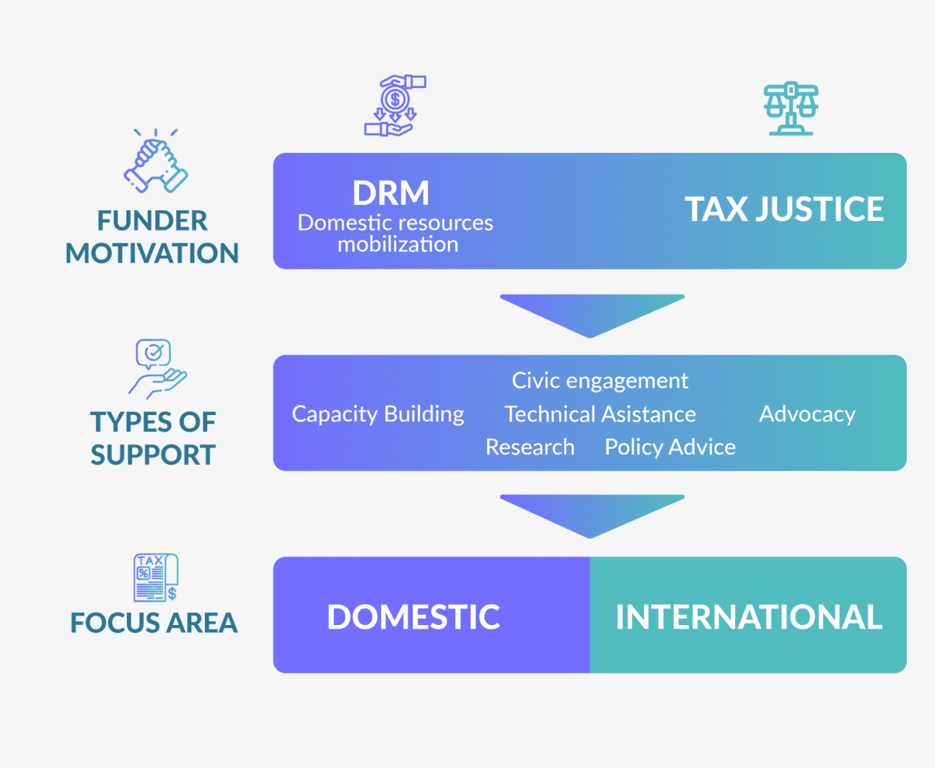

Note that the scan focuses more on funding to the international dimensions of tax: country-level funding is included for comparison. The scan also attempts to categorize elements, such as illicit financial flows (IFFs) separately from more general advocacy and policy.

This summary presents findings from a scan of funding for issues related to international tax justice. See the longer report for more details.

More philanthropies align with “tax justice” than bilaterals or multilaterals

“Tax justice” is less common with public funders: more philanthropies and civil society align with the term compared to governments. Few bilaterals have ever supported a project using the term “tax justice.” Almost all of the bilaterals that have are Nordic countries. Multilaterals also do not use the term to describe their work.

There are six larger funders of international tax justice and countering IFFs

Since 2020, the largest funders of general international tax justice (but not including IFFs, sectors, or countries) are Open Society Foundations (OSF) and Norway, as well as another major human rights funder. If funding for anti-IFFs work is included, Germany, the United Kingdom (UK, and European Union institutions are major funders. Anti-IFFs funding from 2020–2025 totals at least $72 million. Other relevant funders with over $5 million in funding to international tax justice, IFFs, or the intersection of tax and extractives committed since 2020 include the African Development Bank, Finland, Ford Foundation, and Hewlett Foundation.

Funding for international tax justice and anti-IFFs work is over $150 million since 2020

International funding committed to international tax justice since 2020 is at least $55 million. If IFFs, tax and extractives, tax and climate, and Global South regional and country funding are included (but funding for the United States (US) and the UK is excluded) the total is closer to $153 million. Spread across six years (2020-2025 inclusive), this could translate to about $25.5 million a year. This funding is mostly in the form of grants rather than loans, which are more common in domestic resource mobilization (DRM).

Most country-level tax justice support goes to the US

There is substantial new philanthropic funding for tax justice in the US. This funding comes from diverse strategies, including anti-poverty support, economic mobility, equity, and democracy. The Rockefeller Foundation has made a substantial commitment to this area. The funding for the US is also notable when juxtaposed against funding for other countries, including the UK. Total country-level tax justice funding across the Global South is likely lower than funding for the US alone.

Funding for DRM is much larger than that for international tax justice

Funding to DRM in 2020, including loans, was $1.22 billion; in 2021, it was $574.4 million. Assuming 2022–2025 would be like 2021, the total flows from 2020–2025 would be about $4 billion. This would mean tax justice and anti-IFFs funding flows would be about 4% of the total. Using an alternative benchmark based on the grant equivalent of official development assistance from bilaterals and excluding multilateral finance, the percentage would be closer to 9%. International tax justice work is thus a small component of overall tax funding.

Tax justice funding from 2018 to 2023 likely increased and then decreased

Discerning a trend in funding for international tax justice is difficult due to data issues. Two of the main data sets show an increase followed by a decrease. This is similar to the trend in DRM funding in general: funding to DRM increased through 2020 and then dropped sharply in 2021 due to the withdrawal of some of the immediate support (often loans) provided during the pandemic. The levels in 2021/2022 are lower than in 2019, right before the pandemic.

Several philanthropic funders decreased their work in international tax justice in 2023, especially as compared to 2018. Many of these shifted due to internal strategic changes, such as focusing on specific countries or other issue areas. At the same time, a major human rights funder entered during the same time frame providing some counterbalance.

Less funding goes to Asia

Much more funding has been found to go to non-governmental organizations and networks in Africa, Europe, and the Americas. Less funding is reported to countries in Asia in all five of the datasets.

Another way to look at where funding flows is to look at specific organizations receiving funds. Some organizations have funding from many sources, with these being headquartered mostly in Africa and Europe.

MOST Global corporate tax policy funding is not tax justice-oriented

Global corporate tax issues include those related to the distribution of taxing rights across countries, the transfer pricing method of taxation, profit shifting, tax incentives for foreign companies, and tax treaties, among others. Many funders and multilaterals support the current automatic exchange of information and public country-by-country reporting mechanisms maintained by the OECD, which the tax justice community does not fully agree with due to a lack of access for lower-income countries. Most of the funding to global corporate tax policy is not oriented around tax justice but rather other modes such as capacity building.

There are few new funders on the horizon

Of the interviewed funders, only one indicated a new interest in international tax justice specifically. The trajectory of future funding will be influenced by many factors, including decisions within funders we did not interview, the connection to adjacent spaces with better funding (e.g., climate), advocacy, and fundraising. There may be opportunities to increase funding to counter IFFs and support tax and extractives as these issues gain traction. It was speculated that the upcoming Financing for Development conference in 2025 may also influence funding.